The Problem

If you manage devices at customer sites, you've encountered this. Consumer routers and ISP modems ship with addresses from a small pool of defaults: 192.168.1.x, 192.168.0.x, 10.0.0.x. Every site ends up on one of the same few subnets.

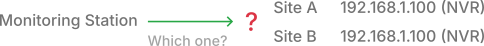

One remote site isn't a problem. Set up a VPN, add a route, traffic flows. But the moment multiple sites share the same address range, you have a conflict that IP routing cannot resolve. A packet destined for 192.168.1.100 has multiple valid destinations. The routing table accepts one entry per prefix. One site works. The others are unreachable.

At 10 sites, you might manage it with careful subnet allocation. At 50 or more sites, it's unmanageable. You can't maintain unique addressing across networks you don't control. You didn't configure these routers. You don't have admin access without visiting the site. Re-addressing a customer's home network to avoid conflicts isn't realistic.

The Second Problem

The devices you need to reach, cameras, NVRs, NAS units, etc., are embedded systems with locked-down firmware. No SSH. No package manager. No way to install VPN software.

Almost all mesh VPNs require software on every endpoint. That works for laptops and servers. It doesn't work for a camera running proprietary firmware.

Why Port Forwarding Fails

Often, the solution is port forwarding. Open ports on the customer's modem and map external ports to internal devices. This exposes those devices directly to the internet, visible to anyone with a port scanner. For cameras and NVRs running firmware with known vulnerabilities, that's a security nightmare.

It's also fragile. When the ISP replaces or resets the modem, all port forwarding configuration is gone. You're dispatching a technician to reconfigure it.

Some protocols don't work at all. Camera streaming protocols like RTSP negotiate additional ports dynamically. Forward the control port and the handshake succeeds, but the video uses ports that aren't forwarded.

And if the customer has double NAT, or the ISP uses carrier-grade NAT, there may be nothing to configure.

The Solution (In Theory)

The solution is to not route local addresses at all.

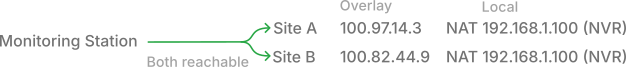

Instead, you assign each local device a unique IP on an overlay network. The device's local address (192.168.1.100) becomes irrelevant. Everything else knows it by its overlay address.

To do this, you place a gateway on the customer's LAN, a Linux device you control. This gateway joins your mesh network and has access to the local devices.

The gateway uses one-to-one NAT to project a mesh address onto each local device. The camera at 192.168.1.100 becomes reachable at 100.97.14.3 on the mesh.

Traffic arriving for the overlay address is translated to the local address. The local device sees a packet from a neighbor on its own subnet and responds normally. No software on the endpoint. No configuration changes on the camera or NVR. It doesn't know it's remotely accessible.

For example, Site A's camera is 100.97.14.3. Site B's camera is 100.82.44.9. Both are physically 192.168.1.100 at their respective sites. The routing conflict is gone.

The Solution (In Practice)

The technology is straightforward. Encrypted tunnels handle the secure transport. Standard NAT handles the address translation. Anyone comfortable with Linux networking can set this up for one site.

The problem is scale.

At 10 devices per site across 100 sites, you have 1,000 configurations to manage. VPN configs, firewall rules, DNS records, access control. Add a device, update the gateway, propagate the change. Remove a technician, revoke access across every site they touched. Something breaks at 2 AM, figure out which of 1,000 configurations drifted.

Doing this manually doesn't scale. The solution is technically valid but operationally unworkable without automation.

The Orchestration Layer

Netrinos is a configuration manager built on industry-standard tools: WireGuard for tunnels, native firewalls for address translation. These are trusted, proven components. Any of them can be configured manually. None of them can solve the conflicting subnet problem on their own at scale. The orchestration is what makes it work.

Register a device ("192.168.1.100 on this site, call it lobby-cam"), and everything is generated and deployed: the VPN peer on the gateway, the firewall rule for address translation, the DNS record so you can reach it by name. All kept in sync across hundreds of sites.

Add a technician to your team and assign them access. They can reach those devices from anywhere. Remove a technician, and their access is revoked. No per-site VPN credentials to manage, no firewall rules to maintain.

Health monitoring shows which gateways are online, which devices are reachable. When something goes wrong, you know where to look instead of checking 1,000 configurations by hand.

In Production

A security integrator managing residential camera systems has been running this across 300 sites with over 3,000 cameras for two years.

Before: open ports on every ISP modem, cameras exposed to the internet, technician dispatched whenever an ISP reset a modem.

After: no open ports on customer equipment, all traffic encrypted end-to-end, attack surface went from 3,000 devices on the public internet to zero. ISP can swap the modem or reset it to factory defaults. The gateway reconnects automatically. Technicians in the field access any camera by its DNS name, from any location, through the same encrypted mesh. No exposed ports, no shared credentials, no VPN configs to hand out.

Adding a new site means dropping a gateway on the customer's LAN. It picks up a DHCP address and calls home. Back at the office, register the devices from your dashboard, and they're immediately reachable.

Closing

Every service company managing devices at customer sites runs into this: the networks they need to reach all look identical. Overlay addressing solves it. The local IP becomes an implementation detail, and the devices you need to reach get unique addresses that route without conflict.

The technology exists. The hard part is orchestrating it across hundreds of sites without manual intervention. That's what Netrinos and Virtual Devices do.

Netrinos runs on Windows, macOS, and Linux. Start a 14-day free trial, no credit card required.