The Problem

If you manage devices at multiple customer sites, you already know this problem. Every consumer router and ISP modem ships with the same default subnet. The specific range varies by manufacturer (192.168.1.0/24, 192.168.0.0/24, 10.0.0.0/24), but the result is the same: every site ends up on one of the same few subnets.

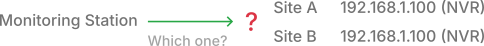

Security integrators, MSPs, AV installers, home automation companies. Anyone who deploys equipment at residential sites encounters this immediately. The NVR at one customer's home is 192.168.1.100. The NVR at the next customer's home is also on 192.168.1.x. And the one after that.

One remote site isn't a problem. Set up a VPN gateway, add a route for 192.168.1.0/24, and traffic flows to the right place. Two sites with different subnets, still fine. But the moment two sites share the same address range, you have an ambiguity that IP routing cannot resolve.

A packet destined for 192.168.1.100 has two valid destinations. The routing table accepts one entry per prefix. One site works. The other is unreachable.

At 50 or 300 sites, the problem is absurd. You can't maintain unique subnet assignments across networks you don't control. You didn't configure these routers. You don't have admin access to most of them. And re-addressing a customer's home network to avoid conflicts with your other customers isn't realistic.

There's a second problem. The devices you need to reach, cameras, NVRs, NAS units, etc., are embedded systems with fixed firmware. There's no SSH, no package manager, no way to install a WireGuard client. You need to reach them, but they can't participate in any overlay network directly.

Why Traditional Approaches Fail

Port forwarding

The most common workaround. Open ports on the customer's ISP modem and map external ports to internal devices. This works until the ISP replaces or resets the modem. When that happens, the port forwarding configuration is gone. You're dispatching a technician.

Port forwarding also breaks multi-port protocols. RTSP, the protocol used by most IP cameras for video streaming, uses TCP (typically port 554) as a control channel, but delivers the actual video over RTP on separate UDP ports. These ports are dynamically negotiated during session setup, and they span a wide range. Port-forward TCP 554 and the RTSP handshake succeeds, but the RTP media arrives on UDP ports that aren't forwarded. The control session connects. The video never arrives.

And that assumes a single NAT. Many sites have a security firewall behind the ISP modem, or a cellular modem in front of it. Double or triple NAT means configuring port forwarding on two or three devices in series, any of which can be reset or replaced independently. If the ISP uses CGNAT, the outermost NAT is on the ISP's infrastructure and you have no options.

Subnet routing

Route all of 192.168.1.0/24 through a VPN node at the remote site. This works for exactly one site. The routing table accepts one next-hop per destination prefix. When two sites share the same range, you can route to one or the other, not both.

Re-addressing

Assign each customer a unique subnet so addresses don't overlap. This is the theoretically correct answer. It's also operationally impossible at scale. You don't own these networks. The customer's ISP modem manages DHCP. Their phones, laptops, and smart speakers expect the existing configuration. Re-addressing 300 customer networks and maintaining a master subnet allocation is not a real solution.

Overlay Addressing with 1:1 NAT

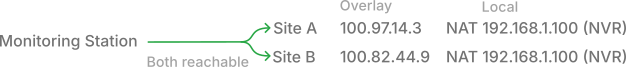

The approach that works is to stop trying to route to local addresses entirely. Instead, assign each remote device a globally unique IP in a separate address space (an overlay network) and translate between the overlay address and the local address at each site.

You place a device on the customer's LAN: a Raspberry Pi, a spare PC, any Linux box. This device connects to your mesh network via WireGuard. It also has a connection to the local network where the target devices sit.

For each device you want to reach, you assign an address from the overlay range. RFC 6598 reserves 100.64.0.0/10 for Carrier-Grade NAT, providing roughly 4 million addresses. This range is almost never used on customer LANs, so it won't collide with existing devices. And because the overlay addresses only exist inside WireGuard tunnels, they never appear as raw IP on the internet, so there's no conflict with ISPs that use CGNAT on the WAN side. Each camera, NVR, or NAS gets a unique address in this space, regardless of its local IP.

The gateway device performs 1:1 NAT. Traffic arriving for 100.97.14.3 is destination-translated to 192.168.1.100, and the source is masqueraded to the gateway's own LAN address. The local device sees a packet from a neighbor on its own subnet and responds normally. Connection tracking reverses both translations on the return path. A single gateway holds multiple overlay addresses, one per device behind it, so each camera, NVR, or panel gets its own IP and DNS name on the mesh.

The local device has no awareness of this. It receives packets from a local IP (the gateway's LAN interface) and responds normally. No software, no configuration changes, nothing installed on the endpoint.

The local IP address becomes an implementation detail. Only the NAT rule on the gateway cares that the NVR is at 192.168.1.100. Everything else on the overlay network knows it by its unique address. Site A's NVR is 100.97.14.3. Site B's NVR is 100.82.44.9. Even the monitoring station itself can be on 192.168.1.x. It doesn't matter. The conflict is gone.

The NAT itself is trivial. Anyone can write an nftables rule. The hard part is automating it across hundreds of sites: key generation, peer distribution, NAT rule management, DNS assignment, health monitoring, roaming technicians who need access from the field, all without manual intervention. Each device requires a WireGuard peer, a DNAT rule, and a DNS record. At 10 devices per site across 300 sites, that's 3,000 sets of configuration to generate, deploy, and keep in sync.

In Production

A security integrator managing residential camera systems operates approximately 300 customer sites with over 3,000 cameras, NVRs, etc. Every site has a standard ISP modem handing out addresses in 192.168.1.0/24.

Before: open ports on every ISP modem. Cameras, many running firmware with known vulnerabilities, exposing port 80 directly to the internet. When the ISP replaced or reset a modem, all port forwarding configuration was lost. A technician was dispatched to reconfigure it.

After: a gateway device at each site connects to the monitoring station through an encrypted WireGuard mesh. Each camera has a unique overlay address. The monitoring station accesses any camera by its overlay IP or DNS name.

The security posture changed. Cameras that were previously exposed to the internet, reachable by anyone with a port scanner, are now invisible. No open ports on customer equipment. All traffic encrypted end-to-end inside WireGuard tunnels. The attack surface went from 3,000 devices on the public internet to zero.

Operationally, truck rolls for connectivity issues stopped. The ISP can swap the modem, change the customer's public IP, or reset the device to factory defaults. The gateway reconnects automatically, and the overlay addresses don't change. Sites with dual-WAN failover just work: the gateway uses whichever uplink is available. A technician in the field connects to the mesh and accesses any camera by its DNS name, from any location, without VPN credentials per site or firewall rules to maintain.

Adding a new site means dropping a gateway on the customer's LAN. It picks up a DHCP address and calls home. Register the devices from your dashboard, and they're immediately reachable. This deployment has been running in production for over two years.

Clarifications

Not a full mesh. Customer gateways don't know about each other. A gateway at Site A has no awareness of Site B. Only the monitoring station and technicians assigned to the sites can reach its devices. Access control enforces this: each participant on the mesh sees only what they should. This is the correct topology for managing customer equipment, not a limitation.

NAT is still NAT. DNAT with masquerade passes all ports and protocols, so multi-port protocols like RTSP should work: the dynamically negotiated RTP ports pass through without explicit forwarding rules. Protocols that embed IP addresses in their payload (RTSP includes the device's local IP in SDP) or use IP-based authentication may need testing.

Requires a foothold device. You need a device on the remote LAN to run the VPN and NAT. At scale, a dedicated Linux device makes sense: a Raspberry Pi, a small appliance, a spare PC. But the same virtual device capability works from any Netrinos client on Windows, macOS, or Linux. Either way, if there's nothing you can control at the target site, this approach doesn't help.

Address space. The overlay uses the 100.64.0.0/10 CGNAT range (RFC 6598). This range is not for use on customer LANs, so collisions with local devices are unlikely. Overlay addresses are encapsulated inside WireGuard tunnels and never appear on the public internet, so ISP-level CGNAT will not conflict.

Under the Hood

Netrinos is a configuration manager built on industry-standard tools: WireGuard for tunnels, nftables on Linux, PF on macOS, WFP on Windows. These are popular, trusted, proven components. None of them can solve the conflicting subnet problem on their own. The orchestration is what makes it work, generating the right configuration across hundreds of devices and keeping it in sync.

The implementation uses three components, all generated from a single device registration.

A WireGuard peer, auto-generated for each virtual device:

[Peer]

PublicKey = <generated-per-device>

AllowedIPs = 100.97.14.3/32A DNAT rule and masquerade (nftables on Linux):

# Translate destination to local device

ip daddr 100.97.14.3 dnat to 192.168.1.100

# Masquerade tunnel traffic going to LAN

iifname "wg0" oifname != "wg0" masqueradeA DNS record mapping a human-readable name to the overlay address:

lobby-cam.downtown.myco.2ho.ca → 100.97.14.3Register a device ("192.168.1.100 on this site's LAN, call it lobby-cam"), and all three are generated and deployed. No manual WireGuard configuration, no hand-written firewall rules, no DNS zone editing.

Closing

Every service company managing devices at customer sites runs into this: the networks they need to reach all look identical. Overlay addressing with 1:1 NAT solves it. The local IP becomes an implementation detail, and the devices you need to reach get unique addresses that the rest of the network can route to without ambiguity.

The components are standard: WireGuard, nftables, DNS. The hard part is orchestrating them across hundreds of sites, keeping keys rotated, NAT rules consistent, and DNS records in sync, without manual intervention. That's the problem worth solving.

This is how Netrinos Virtual Devices work. The software runs on Windows, macOS, and Linux, with a 14-day free trial.